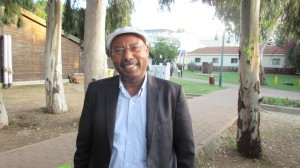

Avraham’s miracle

“It’s a miracle,” says Avraham Neguise in a quiet, modest tone of voice that downplays the hugeness of his hard-fought achievement.

The miracle the rookie Knesset Member is referring to is the government’s landmark November decision to allow 9,000 Ethiopian Jews, who were previously not recognized as Jews, to immigrate to Israel.

Some of them have been cut off from siblings, parents, children and other close family members for as long as 15 years.

“One of those stranded in Ethiopia is an elderly man who for years hasn’t seen his eight children living in Israel. He hasn’t even met most of his 52 grandchildren,” says Neguise, giving an example of the unconscionable situations endured by many families.

The reason these families became separated goes back to a shift in government policy that followed the mass airlifts of 8,000 Ethiopian Jews to Israel in 1984 and 14,000 in 1991. During those operations and in the years in between, some of those allowed to come were of mixed Jewish and non-Jewish lineage.

Then, in 2003, the Sharon government clamped down ‒ only those Ethiopians who could prove they were Jewish according to strict criteria, specifically that their mother was Jewish, would qualify. Despite objections that this ruling contradicted the Law of Return, which only requires that a single grandparent on either the mother or father’s side be Jewish in order for a person to be allowed to make aliya, this criteria was renewed by the Netanyahu government of 2010.

The result of the new criteria was disastrous. Many Ethiopians, planning to join their family members in Israel, had sold their land and livestock and set out from distant villages in the countryside for the Israel Embassy in the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa. When they arrived, they suddenly discovered that they could not receive an aliya visa.

Since most were farmers, they were now without a way of making a living. They settled into ramshackle huts adjacent to the embassy where they have remained ever since, living in abject poverty and relying on funds sent from their relatives in Israel. Yet, they have clung to the hope that things would one day change and many regularly visit a synagogue that they set up in a large tent decorated with Israeli flags.

In Israel, their families protested, but the government remained indifferent to their plight. Demonstrations were periodically held by student groups supported by a number of notable Israeli figures such as former Supreme Court Judge Meir Shamgar and Rabbi Menachem Waldman, who the government commissioned to conduct a survey of the Ethiopian Jewish population in the early 1990s (see sidebar) but to no avail.

At the forefront of these protests was Neguise, 57, an activist who immigrated to Israel in 1985 and who founded in 1991 an NGO known as South Wing to Zion, which advocated on behalf of Ethiopian Jews.

Neguise did succeed in getting the Israeli government to speed up the aliya and absorption of Ethiopian Jews who met its criteria, but when it came to bringing the rejected ones, he ran into a brick wall. In 2014, the government officially announced that no Jews remained in Ethiopia and shuttered the immigration centers in Ethiopia run by the Jewish Agency.

The historic Ethiopian immigration saga had seemingly come to a close.

Then came the Israeli elections of 2015. Neguise decided to toss his hat into the ring and managed to capture the 27th spot on the Likud list and became the last candidate on the party’s list to be elected to the Knesset.

Soon after the elections, the Israeli Ethiopian community was thrust into the public spotlight when a video camera recorded police officers beating up an Ethiopian-Israeli soldier. Riots erupted. Ethiopian-Israeli protesters claimed that the incident was just one of many acts of discrimination the community has experienced over the years.

At a loss on how to quell the unrest, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu turned to his rookie MK for advice. Naguise drew up a list of legislative proposals that he felt would improve the conditions of the Ethiopian community. He also explained to his Knesset colleagues that the government’s refusal to allow members of the community stranded in Ethiopia to come to Israel was a festering sore that exacerbated the tension.

“Soldiers serving in the army here with brothers over there who weren’t allowed to come on aliya triggered much anger,” explains Neguise to The Jerusalem Report.

He also initiated a fact-finding mission to Ethiopia with the participation of three other Knesset Members. They spent Shabbat with members of the community and visited their homes.

“They were shocked by what they saw,” recalls Neguise. “After seeing the awful conditions under which they lived and hearing about their longing to see their family members, the Knesset Members were vehement in requesting that the government urgently change its policy.”

With the backing of the MK delegation, Neguise once again requested recognition of the stranded community. At long last, the government relented.

“Not only did the government agree, it did so unanimously,” he relates with satisfaction. The government decision, for the first time, enables Ethiopians who have Jewish lineage on their father’s side to come to Israel. Their non-Jewish spouses and common children will also be included. The first group is expected to arrive in March 2016.

“The government timetable calls for all of them to be here within five years, but it is quite possible that they will get here much sooner,” says Neguise.

Now that Neguise has achieved one goal, he realizes that he still has lots of work cut out for him. The Ethiopian community, numbering today about 130,000, lags behind the rest of the country in many key areas.

To close the gap, Neguise has introduced legislation that aims to improve educational and job opportunities for the Ethiopian community. To implement this program, the government has allocated NIS 530 million to be spent over the next four years.

He also is tackling head on other points of heated contention.

One is the issue of school discrimination. Until now, certain schools have managed to exclude Ethiopian students without suffering serious repercussions. “You can say to a school principal a million times that what he is doing is racism but it doesn’t help. There is no real punishment,” notes Neguise who has proposed a law enabling the Education Ministry to cut off funding if there is evidence of discrimination.

Neguise also has introduced legislation that aims to prevent the fostering of attitudes that lead to discrimination.

“The idea is that the school curriculum will include lessons about the heritage of all the different Israeli ethnic groups. If people know more about each other’s heritage, including that of Ethiopians, it will create mutual respect,” observes Neguise, who has a PhD in education.

To remedy the problem of police violence, Naguise has proposed that police officers wear body cameras. He points out that a research study conducted in California showed that when there is video documentation of police-citizen interactions, false accusations of police misconduct were reduced by 80 percent and acts of actual police violence dropped 60 percent. “The police themselves have welcomed this approach and a pilot study is now underway in Netanya and Rishon Lezion,” he reports.

Naguise admits that he didn’t expect to see so many positive things on behalf of the Ethiopian community happen so quickly. Less than a year ago, he spent his days working quietly in the small South Wing of Zion office in Jerusalem, patiently receiving visits from individual Ethiopians looking for help in dealing with government bureaucracies. Now, as he tours the country and meets with large gatherings of Ethiopian Israelis he often receives a hero’s welcome.

“The Knesset Members who visited Ethiopia apologized to the community for making them wait so long,” says Neguise. “Now that we can put that issue aside, we can concentrate on completing the task of integrating the Ethiopian community into Israeli society.”

SIDEBAR

As the plane travels from Addis Ababa to Tel Aviv, Rabbi Menachem Waldman, looking out the window, notices a river flowing westward. “That is the Guang River, which flows into the Nile,” he says, pointing out that Ethiopian Jews for centuries considered a spring that was the source of the Guang to be a holy spot. “They believed that they would one day follow that river on their way back to Jerusalem.”

Waldman was one of the first and only Israelis to meet Ethiopian Jews in their villages during the early 1990s when he was sent by the Israeli government to compile a report on their status. “I was struck by how strong their desire was to come to Israel,” says Waldman who notes that now that they have all come to Israel and adjusted to the modern religious practices of Judaism, much of their unique lifestyle has vanished.

Waldman’s description of how these communities lived prior to re-connecting with their Jewish brethren is documented in a book called “Masa el Shearit Yehudei Ethiopia” (Journey to the remnant of the Jews of Ethiopia) being published (in Hebrew) this month by Yad Ben Zvi.

B.D.