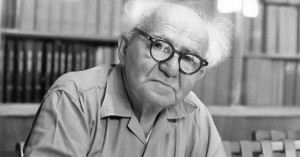

If visitors from outer space were to eye Israel the way novelist William Burroughs suggested they would view the world (“After one look at this planet any visitor from outer space would say ‘I want to see the manager.’”) there is little doubt that the Israeli manager would be David Ben-Gurion, the country’s revered founding prime minister, whose leadership shoes have never quite been filled ever since, not even by his notable prodigy Shimon Peres.

Unfortunately, for extra-terrestrial guests and perplexed Israelis alike, Ben-Gurion passed away in 1973.

But wait a minute, what if it was possible to bring him back and hear what he has to say about Israel’s current problems? About the Palestinian-Israeli conflict for instance?

Ben-Gurion, Epilogue, a new Israeli documentary written and directed by Yariv Mozer, tries to a certain extent to do exactly that. The film is based on footage of an in-depth recently-discovered interview with Ben-Gurion that has never been seen before.

The year is 1968. It is 20 years since Israel declared its independence, one year since the country captured territories from Egypt, Jordan and Syria. Ben-Gurion, 82, has resigned from the government and is living alone in his desert kibbutz, uninhibited by political constraints, free to speak his mind.

Most of the film is comprised of Ben-Gurion’s uninterrupted answers to questions from ethnographer Clinton Bailey. But occasionally the filmmakers offer subtle interpretations. For instance, when Ben-Gurion talks about why, despite strong opposition from Holocaust survivors, he established ties in the 1950s with West Germany, Ben-Gurion doesn’t mention one possible reason – assistance from German nuclear scientists in building Israel’s capability. That suggestion comes from a juxtaposed German tv news report.

When it comes to the territories captured in the 1967 war, Ben-Gurion is quite straightforward. So much so, that it will be tempting for present-day viewers, to pluck out a line or two and use them to re-inforce their own political agenda.

When he says “If I would have a choice between peace and all the territories which we conquered last year (during the 1967 war) I would prefer peace,” it will be music to the ears of people on the left.

But when, in the same breath, he qualifies that by saying that he would not withdraw from certain territories – (East) Jerusalem and the (formerly Syrian) Golan Heights — the ears of those on the right will undoubtedly perk up.

It would be unwise, however, for anyone to suggest that political decisions today can be based on the political realities of nearly 50 years ago.

And filmmaker Yariv Mozer has been wise enough to not overdo the political and instead use the six hours of raw footage at his disposal, along with period newsreels, to create a character study with uncanny contemporary resonance. From one utterance to another, we slowly get to know a leader who placed a high value on setting a personal example, was intimately familiar with other cultures, and offered his people a moral vision.

These characteristics are particularly striking compared to so many present day politicians, be they lawyers or real estate tycoons.

The contrast between them and Ben-Gurion can be quite stunning. Ben-Gurion worked as a farm laborer when he first arrived in the country in 1906; he quit the government for two years during the 1950s to return to farming the desert, and, even as a retiree, he pitched hay and planted trees.

“I want to live in a place where everything is created by your own work… where me and my friends can say we did it!…We created everything…The trees that I see I know that I have planted them.” (says Ben-Gurion).

When asked about the meaning of meditation, Ben-Gurion, who was as well-versed in the Buddhist sayings of Dhammapada as he was in those of the biblical prophet Jeremiah, patiently explains the difference between the Buddhist and Jewish traditions.

In one delightful scene, in which the film wanders away from the desert hut where the lost interview was filmed, we see Ben-Gurion dressed in Buddhist garb visiting a shrine in Burma (today Myanmar) and conversing with Burmese prime minister U Nu , about whether or not it will be possible to “get rid of all of the world’s troubles” by “getting rid of the word ‘I’ and I consciousness…”

Evident in this scene is the warmth and high esteem with which Ben-Gurion was held by U Nu, as he also was by many other international leaders, especially heads of the newly independent African states. Ben-Gurion mentions that he wants Israel to be a nation of “higher virtue”, and indeed, during his 13 years as prime minister, Israel led the world in providing agricultural and medical assistance to post-colonial Africa.

Ben-Gurion also managed to gain the respect of some Arab leaders, including Musa Alami, the then de facto Palestinian leader. Alami mentions a 40-year friendship with Ben-Gurion and remarks that he liked Ben-Gurion for his frankness even if “his frankness was almost frightening.”

That honesty was what Ben-Gurion was all about. During his tenure, he kept the country in good standing with most other nations around the world, as well as unified within.

He is reluctant to take credit however for much of what he has done. “I didn’t guide Israel, I guided myself,” he says as he tries to steer credit to the pioneer farmers who arrived as far back as 1870. He points out that when he met Albert Einstein he asked him if it was true that he had come up with the theory of relativity completely on his own. Einstein, he recalls, said that he built his theory on the basis of experiments carried out by others.

Clearly though, without Einstein there would be no theory of relativity.

Similarly there can be little doubt about the role of Ben-Gurion in the history of Israel. Without Ben-Gurion, it’s hard to imagine that the modern state of Israel could ever have been created.

Bernard Dichek